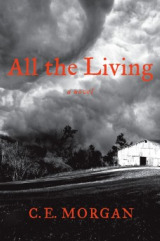

Today at The Second Pass I consider C.E. Morgan’s first novel, All the Living, in the context of other fiction that takes up the question of faith — and as an example of what Marilynne Robinson has provisionally called “cosmic realism.”

Today at The Second Pass I consider C.E. Morgan’s first novel, All the Living, in the context of other fiction that takes up the question of faith — and as an example of what Marilynne Robinson has provisionally called “cosmic realism.”

An excerpt:

Marilynne Robinson is the rare contemporary writer who has dared to devote entire novels largely to the question of faith. Gilead, presented as a dying pastor’s letter to his young son, sustains a subtle but tenacious momentum completely dependent on its narrator’s eloquence, insight, and complexity of thought. Yet fiction that directly engages religion can descend so speedily into sentimentality or sermonizing, or even caricature, that the stories most effective at compelling the agnostic reader to consider the possibility of God generally seem at the outset to be about something else. Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair, for example, transforms from an obsessive chronicle of a jilted lover’s efforts to discover who is sleeping with his beloved into an atheist’s unwilling screed against a deity he doesn’t believe in: “I hate you as if you existed.” Peter De Vries’ brilliant The Blood of the Lamb invokes religion from the start, but with the ironic (and hilarious) detachment of someone raised in, but estranged from, the church — until he needs a higher power to lash out at when his little girl is stricken with cancer. Cormac McCarthy’s The Road depicts a father and son trekking through charred forests in a frigid post-apocalyptic world that promises a life of scavenging and likely death at the hands of cannibals, and it is only when the man kills to protect the boy, saying, “I was appointed to do that by God,” that the reader is implicitly called upon to consider what sort of creator would allow humanity to exist in a state so bereft of hope.

Although his setting is singularly dire, McCarthy is of course far from alone in tying religious concerns to nature. Last year Robinson, in a review of Annie Dillard’s The Maytrees, tentatively identified an entire genre, “cosmic realism,” in which the physical world is “primordial, archaic, full of the fact of time past and persisting, unchanging, changing everything.” As Francesca Mari has observed, “Robinson’s labeling is cautious — perhaps because it approaches self-categorization. But the classification is inspired. [Cosmic realism] encompasses a range of description-driven novels steeped in transience and obsessed with iterations of ephemerality. Their substance is more thought than action, and the thought is almost as much perception as it is reflection.” These works, says Mari, owe a great deal to the Transcendentalists. At their best, the books evoke landscapes and moods to summon questions of being at the core of us all; at worst they are freighted with false solemnity, and objects and moments too trite or insignificant to bear the weight of the symbolism forced upon them.

C. E. Morgan’s contemplative and atmospheric first novel, All The Living, is cosmic realism subtly tinged with the anger of The End of the Affair or The Blood of the Lamb. Like The Road, it edges into spiritual concerns slowly, seeming at first to be a story about a young woman, Aloma, torn between her desire for independence and her passion for a man. Love, or at least lust, is winning as the story begins. Aloma has joined her lover, Orren, at the ragged and desolate Kentucky farmhouse where he grew up and has been living since his family was killed in a tragic accident a few months before.

See also Zoë Slutzky’s review for Bookforum and Beth Kephart’s for The Chicago Tribune.