I don’t measure fiction by the same aesthetic metrics as James Wood, but I read him, even when his judgments rankle. Any impassioned Wood critique is far superior to a hundred courteous hand-clappings.

It’s especially interesting to see Wood building, in the latest New Yorker, on the grudgingly admiring essay about J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace (“a very good novel, almost too good a novel”) that appeared in The Irresponsible Self, and extending some of the theses he began to formulate in his review of Elizabeth Costello.

In Coetzee’s novels, Wood observes, “emotions like shame, guilt, and disgrace surge beyond rational discussion.” Placing Diary of a Bad Year in the larger context of the Nobel laureate’s body of work, he argues that “Coetzee has always been an intensely metaphysical novelist, and in recent years the religious coloration of his metaphysics has become more pronounced.”

The pieties of current criticism are supposed to forbid one to inquire about Coetzee’s relation to this strain of theology. We are warned that it is naïve to confuse author and character, even when — especially when — that character is also a novelist. But if Coetzee’s novels deflect such inquiries, they also invite them, not least because of the provoking extremity, even irrationality, of their ideas. In the last entry of this novel, “On Dostoevsky,” Señor C writes:

I read again last night the fifth chapter of the second part of The Brothers Karamazov, the chapter in which Ivan hands back his ticket of admission to the universe God has created, and found myself sobbing uncontrollably.

It is not the force of Ivan’s reasoning, he says, that carries him along but “the accents of anguish, the personal anguish of a soul unable to bear the horrors of this world.” We can hear the same note of personal anguish in Coetzee’s fiction, even as that fiction insists that it is offering not a confession but only the staging of a confession. His books make all the right postmodern noises, but their energy lies in their besotted relationship to an older, Dostoyevskian tradition, in which we feel the desperate impress of the confessing author, however recessed and veiled.

I’ve yet to get my hands on a copy of Diary of a Bad Year, but Wood’s critique puts me in mind of Peter Brooks’ Troubling Confessions: Speaking Guilt in Law and Literature, the most useful work of criticism I own, and the only one I revisit annually.

The book bears an approving dust jacket blurb from J.M. Coetzee, and cites him throughout. Here’s a passage Brooks quotes from “Confession and Double Thoughts: Tolstoy, Rousseau, Dostoevsky“:

The end of confession is to tell the truth to and for oneself. The analysis of the fate of confession that I have traced in three novels by Dostoevsky indicates how skeptical Dostoevsky was, and why he was skeptical, about the variety of secular confession that Rousseau and, before him, Montaigne attempt. Because of the nature of consciousness, Dostoevsky indicates, the self cannot tell the truth to itself and come to rest without the possibility of self-deception. True confession does not come from the sterile monologue of the self or from the dialogue of the self with its own self-doubt, but … from faith and grace.

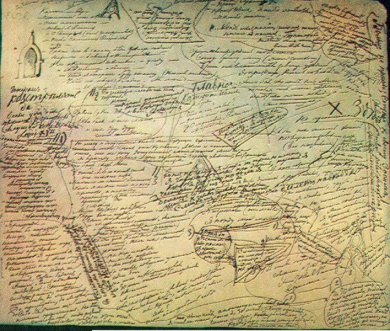

The image is of Dostoyevsky’s notes for chapter 5 of The Brothers Karamazov.