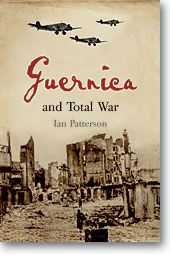

Below Valerie Trueblood, author most recently of the novel Seven Loves, praises Ian Patterson’s Guernica and Total War, an indictment and examination of war from the skies, just out from Harvard University Press last month.

I wonder why in this country we don’t hear the word “wartime.” Here we are in year five of one war and year six of the other. Art is long, but how many of the books on reading lists this summer will last as long as these two wars already have?

I wonder why in this country we don’t hear the word “wartime.” Here we are in year five of one war and year six of the other. Art is long, but how many of the books on reading lists this summer will last as long as these two wars already have?

Here’s one, by someone whose mind is very much on wartime, and painfully on the men, women and children we try to keep safe by calling them civilians. Ian Patterson’s Guernica and Total War is about bombs dropped onto civilians from the sky. It is short, dense with facts and stories, angry — if anger can be so clearheaded — and profound.

After the bombing of the Basque village of Guernica in 1937 (the work of German planes in support of Franco in the Spanish Civil War), the British quickly supplied themselves with the term “frightfulness,” and just as quickly, the word exhausted itself. Then there seemed to be no word for what had been felt, and perhaps that was the beginning of its not being so clearly felt any more.

And in fact where that feeling of horror resurfaces today — it is to our credit that we have a remnant of it — there are always those telling us we’re wrong to think obliteration is the nature and goal of war. War has its rules, the Geneva Conventions exist, and so on. A usually responsible defense analyst told a recent reviewer of Patterson’s book that the comparison of Baghdad to Guernica (which the author makes in his introduction and conclusion) implies that moral progress is impossible in the conduct of warfare. What to say to that. Yes, that certainly would be the implication.

The book has much to say to us in the U.S., we who are shopping our way through our wars and finding next to nothing in the newspapers about our bombing runs. But the British, too, get a long hard stare, because of a belief that got its start at the time of Guernica: that this new kind of bombing would demoralize lesser societies — and might reasonably be used by the civilized powers for that purposeâ€â€but would never have that effect on them. Needless to say, it took Guernica, a European target, to trigger outrage and sorrow; earlier in the century, few noticed when towns and tribes in Africa and Waziristan were kept under control by British bombs. Of the “natives” disciplined in this way, one flight commander said, “No magic survives a good bombing.”

The frankest and least euphemistic statements from the early air warriors are those of Mussolini’s sons, airmen who bombed Abyssinia in the thirties. Vittorio: “It was great fun.” And Bruno:

We had set fire to wooded hills, to the fields and little villages… It was all most diverting… After the bomb-racks were emptied I began throwing bombs by hand… I had to aim carefully at the straw roof…the wretches who were inside…jumped out and ran off like mad. Surrounded by a circle of fire about five thousand Abyssinians came to a sticky end.

For a while, as Patterson’s book shows us, people did have some sense that a terrible era had begun, congenial to such men as the Mussolini brothers, and worse, to the states that put them in the cockpit. Then came World War II, with its sufferings still being unearthed and explained today. Then came smart bombs. Smart bombs, dumb countries. As for us, so many are fixed on what was done to us on 9/11. The deliberateness of it is a prolonged shock. We can’t, as a population, seem to connect our own shock and misery to that of those just like us being repaid in spades for it. Patterson invokes Martha Gellhorn’s curt term for a mute citizenry: “the led.”

Four years after the fact, many of us have forgotten that the U.N. covered up its reproduction of Picasso’s giant Guernica during Colin Powell’s testimony in 2003. Indeed, many of us, including the media, find it convenient to forget that we’re still carrying on two wars.

Patterson’s book deals with the attention artists and writers, in particular, paid to aerial bombardment after Guernica, how they labored to send up into the smoke some signal of their own that things would never be right again. His quietly fierce book takes the reader through the works that made clear what such bombs meant to the people first hearing of them, and shaped much of the end-of-the-world literature of the last century. The “Further Reading” section is a treasury, the list of novels, most of them unfamiliar to this reader, an education in itself.