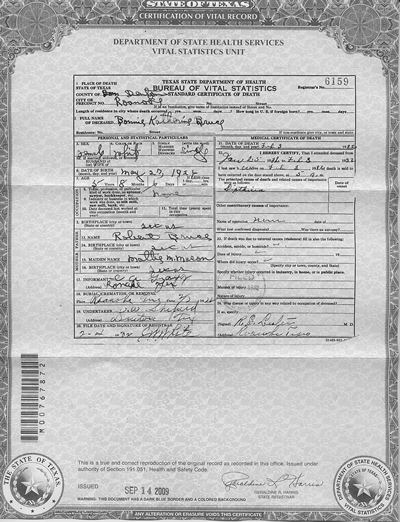

According to her death certificate, my mother’s half-sister Bonnie died of diphtheria — “the deadly scourge of childhood” — at five years old, in a town not too far from Dallas.

According to her death certificate, my mother’s half-sister Bonnie died of diphtheria — “the deadly scourge of childhood” — at five years old, in a town not too far from Dallas.

An aggressive vaccination campaign began in the region around the same time, but perhaps it took a while for word to reach the provinces, or maybe traveling for the shot seemed too cumbersome or securing it was too costly, or the people she was boarding with just didn’t have the energy to care about someone else’s little girl.

The year was 1932. The Great Depression was in full swing and abandonment was on the rise. Bonnie’s parents had already divorced a few years before, leaving her to live as a boarder by the time of the 1930 census.

It’s unclear who was caring for her toward the end of her short life.

Judging from studies of children’s living conditions at the time, Bonnie’s predicament was not terribly unusual.

By 1930 most states had passed compulsory school attendance laws for those under sixteen, established public high schools (although many were segregated), and placed restrictions on the industrial employment of young people under fourteen years of age. In addition, medical science had made great strides in treating and preventing childhood diseases such as diarrhea, rickets, and diphtheria.

Child welfare experts attending President Herbert Hoover’s 1930 White House Conference on Child Health and Protection pointed to the progress that had been made for American children. In his opening address, Hoover waxed sympathetic about the value of children, but there were few positive results from the 1930 conference. The Hoover administration seemed to turn a blind eye to the worsening economic conditions for youngsters and their families. Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur, a medical doctor, argued in 1932 that the economic Depression could actually be good for children. Families with less money to spend, Wilbur concluded, would be forced to depend upon each other and live a more wholesome home life.

It was obvious to many others that a growing number of American children and their families were living in miserable conditions during the worsening economic crisis. By the time Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in March 1933 it was clear that children were experiencing some of the Depression’s worst consequences. While the national divorce rate did not rise, desertion became more common. Although infant mortality rates had continued to fall during 1931 and 1932, they were climbing again by 1933 for the first time since such data had been collected in the United States. With unemployment rates at 25 percent, many families that had been middle-class during the 1920s slipped into poverty, contributing to rising incidence of hunger and malnutrition among children and adolescents. Psychological stress on adults resulted in domestic violence and child abuse. School districts ran out of money, classrooms became more crowded, school years were shortened, and many young people dropped out of school to seek work. Cash strapped business owners and parents ignored or intentionally violated existing child labor laws. Franklin Roosevelt noted that one-third of America’s citizens were ill-housed, ill-clothed, and ill-fed. Of those, the majority were children.

For more, see Dear Mrs. Roosevelt: Letters From Children of the Great Depression. I was also interested to read this 1930 Atlantic article on high medical bills and poverty. Amazing how little progress we’ve made.

The image at the top of this post, obviously, is part of a public awareness campaign for polio. I haven’t been able to locate any older diphtheria posters online.