Marie Mockett’s first novel, Picking Bones from Ash, appears later this year (excerpt here). I’ve started talking about it so far in advance not so much because she’s my friend, although she is, but because I’m passionate about the book and want to do everything I can to spread the word.

Below she discusses some of the themes I’ll emphasize at tonight’s Powerful Women event, which will feature Mockett alongside novelist Marlon James (whose The Book of Night Women I can’t recommend highly enough) and photographer Stephanie Keith.

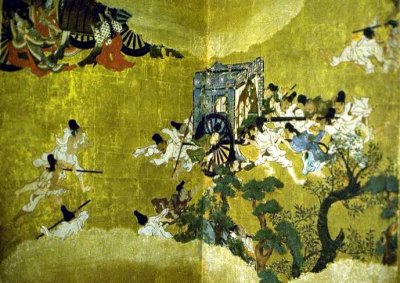

It’s May in Japan and the girls are swaddled in layers of silk and have painted their lips bright red. Everyone is heading for the Hollyhock Festival, but there’s a problem; Lady Rokujo’s carriage is blocking the path of her frenemy, Lady Aoi. At this point, it might be good for Lady Aoi to consider that a few years ago Lady Rokujo killed off another rival via a little spirit possession trick. But competitive girls don’t always think about these things in the heat of the moment. Aoi orders her men to dismantle Rokujo’s carriage; Rokujo deploys her enraged spirit a few days later to tackle Aoi’s body and literally frighten her to death. While all this is deeply upsetting to the men and women in her circle, Lady Rokujo is neither arrested nor punished. It is simply understood that sometimes a girl can’t help but be overwhelmed by frustration, and woe betide the person who provokes her to extreme rage.

This famous incident takes place in The Tale of Genji, written circa 1000 AD and often considered the world’s first psychological novel. For the next one thousand years, a great many classical and popular Japanese plays, texts and films have depicted exorcism and the quieting of hurt and angry female spirits struggling to express themselves in a society where men have most of the power. This is not to say that Japanese women are powerless. Genji, for example, was written by Murasaki Shikibu — a Japanese woman — a fact that startles some westerners accustomed to thinking of the Japanese as being so repressed as to be unexpressive.

Shikibu, however, was not the only female writer of her period; she had an ongoing literary feud with Sei Shonagon, author of the pithy and witty Pillow Book, which chronicled, among other things, “Words That Look Commonplace but That Become Impressive When Written in Chinese Characters” (something with which a certain generation of tattoo enthusiasts might identify). Shonagon thought that Shikibu took herself too seriously and Shikibu thought that Shonagon was a ditz. Whichever side they have taken in this rivalry, female writers in Japan have had Shonagon and Shikibu as a source of inspiration for over a thousand years. Not many cultures — even western ones — can match that.

My first novel, Picking Bones from Ash, comes out in September, and is about three generations of women in Japan and America struggling with what it means to be talented. One of my characters, Akiko, takes a page from Shikibu’s book and believes that the most important thing a woman can do is to develop her gifts. But Akiko is in Japan, and it’s no coincidence that, as the women in her life struggle to accept the abilities they have been given, they run up against an actual ghost among the family demons.

Along the way to publication, a few editors felt that the ghost in my novel was not “literary.” But anything that scares us — whether it’s a discomfiting nightmare, an enemy’s threat, a future unknown — has the ability to change our behavior, and this is the stuff of the best novels. There must be something deeply unsettling to us about talented girls; they often don’t fare well in fiction. In AS Byatt’s Possession, the poet Cristobel Lamott suffers obscurity and a broken heart after her initially inspiring affair with fellow poet Roland Ash; he goes on to enjoy great fame and a stable marriage. Ditto for Griet in Girl with a Pearl Earring; she helps to birth Vermeer’s masterpiece due to her sensitive eye for color and lighting, but doesn’t manage to make much else of her own, except for a nice marriage with the butcher’s son. And who can forget how Briony, the playwright protagonist of McEwan’s Atonement, disastrously meddles with her sister’s love life? I’ve tried, among other things, to examine the thorny questions surrounding talented girls and the things they fear and the reasons why.