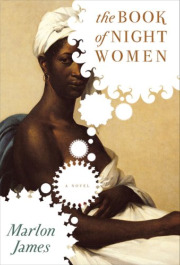

Marlon James set his magnificent second novel, The Book of Night Women, on a Jamaican sugar plantation at the height of 18th century Caribbean slavery.

Marlon James set his magnificent second novel, The Book of Night Women, on a Jamaican sugar plantation at the height of 18th century Caribbean slavery.

The story centers on Lilith, one of several female slaves who plot to overthrow their masters and take over, and is told in a dialect that in other hands would be difficult but here somehow rushes by like water.

“I don’t consider myself a historical novelist,” the author has said. “But I am obsessed with the past. And I am obsessed with stories that weren’t told, or that weren’t told in a good way.” When writing, he keeps in mind an African proverb: “Until the lion’s story is told, the story will always belong to the hunter.”

James and I got to know each other before the book came out, but I’d been anticipating it since picking up his first novel, John Crow’s Devil, in 2006, and I read Night Women, through jetlag, in a single sitting.

Below we discuss his choice of narrator — or the narrator’s choice of him — and much more. You can hear the author read at Housing Works on May 1, at Powerful Women, an event also featuring my friends Marie Mutsuki Mockett (author of Picking Bones from Ash, forthcoming later this year from Graywolf, and Letter from a Japanese Crematorium) and photographer Stephanie Keith.

Your narrator’s voice is incredibly nuanced but also relentlessly candid — a tricky balance that a lesser writer could never maintain — and the result is a perspective that feels completely authentic. The dialect could be difficult coming from another mouth, but her strong point of view overrides all of those concerns so that the language enriches rather than distracting from the story. I hope I’m not giving too much away by revealing that the narrator is a teenage girl. What was the evolution of that voice? Did you start the book from her perspective, or work your way into it?

She is a teenage girl, but also one force-fed brutality and tragedy, which made her grow up fast. Not just the narrator, but the character Lilith as well. I knew she could not be naïve and silly because that kind of childhood was a privilege, not a right. And yet she’s still just a girl in the sense that she has no wisdom from experience. But I’m jumping. I have to say that I did not start the book with her voice at all. I thought this would be a Standard English third person novel and thought so for the first 50 pages of the first draft. When I realized who was supposed to tell the story, even my professor at the time was convinced before I was.

I was the last person to trust her voice, not because there wasn’t a precedent for dialect in storytelling, but because I’m from a background that still looks at dialect as inferior speech whose only place in fiction is to draw attention to itself or make fun of itself in a sort of lyrical blackface. But this narrator would not leave me alone, not until page 50 where I realized that the book as it was could go no further. In desperation I set up a scene where a character, an ex-slave, was interrogated. The interrogation scene, which was supposed to be just a diversion, went on for 500 pages! And even then I wasn’t sure I had a novel.

I had to get over my own prejudices about language. Re-reading Huckleberry Finn and The Color Purple certainly helped. And when I realized I had a novel, I still did not know who was telling the story and would have left it at that until I realized that the novel is also a book about books. Somebody is telling this story, writing this story, somebody, like me, is fated to be witness. After that it was, not easy, but clearer. That resulted in a stronger narrative than those 500 pages, as well as a sense of focus. It was still very important to me that the voice felt true, if not always historically accurate. Jamaican critics are already calling me to task on certain things but they miss the point. My job was to create people who refuse to leave your room even after you’ve closed the book.

Many of your reviews have emphasized the brutality and deprivation of the characters’ lives, and rightly so, but what is even more extraordinary about The Book of Night Women, to me at least, is the tormented romance that drives the last third of the story. Two characters fall into a twisted and passionate affair that sometimes seems like love, but never really can be. The relationship is at least as gripping as what happens between Mr. Rochester and Jane Eyre but fundamentally doomed. Was it difficult to write?

Oh my god it was the hardest thing I’ve ever written in my life. I remember calling friends shouting, “I just wrote a love scene! All they do is kiss!” to which they would respond, “. . . and are they then dismembered?” and I’d go, “No, after that they dance!” It was hard. I resisted it for as long as I could because I didn’t believe in it at first, and even when I did, I couldn’t figure out how to write it. Not until Irish novelist Colum McCann gave me permission by giving me the best writing advice I’ve ever gotten from a writer: Risk Sentimentality.

There’s a belief that sex is the hardest thing for a literary novelist but I disagree: love is. We’re so scared of descending into mush that I think we end up with a just-as-bad opposite, love stories devoid of any emotional quality. But love can work in so many ways without having to resort to that word. Someone once scared me by saying that love isn’t saying “I love you” but calling to say “did you eat?” (And then proceeded to ask me this for the next 6 months). My point being that, in this novel at least, relationships come not through words, but gestures like the overseer wanting to cuddle. Or rubbing his belly and hollering about her cooking, or teaching her how to dance or ride a horse — things reserved for white women.

But is it love, though? Lilith and the overseer have wildly different views. For one, Quinn thinks they have common ground, that the treatment of the Irish has much in common with slavery, when really the two things weren’t even close. But he sees it as a point of connection, a common bond through suffering and prejudice despite his being the kind of person that causes hers. But Lilith knows more than anybody that prejudice comes in varying shades and intensities. It may have been love, I leave that final judgment to the reader, but it’s important that not even Lilith knows what it is.

I think, as a writer, the important thing was to layer the relationship with complexity and contradiction. There were situations where I could have left certain storylines one-dimensional and gotten away with it. I think the relationship is gripping not because they love each other, or think they do (or not) but because even with such a horribly skewed dynamic, hearts do what they want. And people don’t always fit in the roles that have been assigned to them. But of course the relationship is doomed; any slavery love writes its end in its very beginning.

Lilith is not only passionate, but incredibly powerful when moved to anger. Unlike the other women she doesn’t rely solely on strategy and the supernatural to exact revenge, but can assert herself by force when necessary. Afterward she sometimes struggles with the full implications of what she’s done. I know you’ve said that you looked to Toni Morrison and other female writers for help developing her character. Did they help you feel your way toward this aspect of Lilith?

I think so in the beginning. In many ways Morrison’s Sula was a bigger influence on my first novel [John Crow’s Devil] than my second. I re-read Sula recently and was struck, again, by how contrary these women were, how they defied what was expected of them, even by other women, and how especially in that novel, they assumed the right to be everything and nothing at once. That much I think spills over into Book of Night Women. But it did not take me long to realize what a stubborn, self-willed person Lilith was and how she wasn’t about to take any shit, least of all from some male writer.

The best thing I could do for a character like Lilith was to get out of her way, to the point where it felt at times that she was writing me. I don’t think I’ve ever listened to character that way. John Crow’s Devil had strong characters but they never really got out from under the stamp of the author. With this book I sometimes felt like a stenographer taking notes. Or at least an eavesdropper stumbling into conversations and secrets. I think that’s what Toni Morrison and Alice Walker understand, the secret language of women. That it’s not a secret at all; men just don’t know how to listen. And when the men are mostly white and the women mostly black then it’s all the more so.

As for Lilith’s violence, some of that may have also come from reading Sula and Song of Solomon, The Color Purple and Alias Grace, but ultimately it was more from listening to the character. It’s not enough to give Lilith a terrible temper; the writer has to show the consequences of such a thing, good or bad. It would have been too easy to write a one-note character in a slavery novel — the topic is so contentious that I would have gotten away with it. But that would have been dishonest and if it’s one thing I’ve learned from women writers it was to be brutally honest with female characters at the risk of people dismissing them as the very stereotypes they defy.

I’ve heard people call Lilith a bitch and I’m not surprised. But they don’t know her stakes or the stakes for any black woman in the 18th century. It was still hard, or rather it would have been easy, to fall into any of the traps with female characters; they become too good or too bad or too noble or just plain unreal. Morrison taught me that it’s not the actions that must be grounded in gut truth but the emotions behind them.

At a Girls Write Now event last month you had everyone riveted and laughing as you read one of my favorite sections of the novel, in which Homer teaches the teenage Lilith to read. Their text is Henry Fielding’s Joseph Andrews. Did you choose the book because it was prevalent on Caribbean plantations then? Because you foresaw that the juxtaposition would be so hilarious? Some other reason?

At one point, draft five or six, that novel was Fanny Hill, which led to many tedious passages about women owning their orgasms, which they should of course, but it made for some horrible Sex and the City–pon the massa land! kind of fiction.

Sugar estates were male-driven places so Fanny Hill made sense. But so did Fielding, especially Tom Jones and Joseph Andrews, which would have excited younger men and scandalised older. My reason was also personal. The first time a book ever drove me to write fiction was Tom Jones. For one, literature has never had a greater plot before or since, and two, the book is hilarious.

It’s important to remember that even though these books were instrumental in the night women gaining a sort of independence, they were there originally for the enjoyment of men. I like the proto-feminist subversion of that. My original intent was merely to provide a distraction and add some book pages, but then I thought about what reading did for me and for others, people whose stakes were so much lower than Lilith’s. I also began re-reading these books myself and wondered what happens to a woman who sees these men in books but no such man in a real world overrun by men. All these fictional angels being read by real life devils.

Lilith’s second crisis about men is a literary one — none of the men she reads about seem to be true, but they seem so real that she mourns their non-existence and is enraged by the men she ends up having to bear with.

After we met last year, I pestered you every month or so about your progress on the book. When you’d turned in your final draft, you mentioned that it took two exorcisms — I had the impression you might mean literal ones, and having undergone some myself as a child at the hands of a religious mother I was fascinated, horrified, and deeply curious — to get there. Do you want to talk about that?

I’ve heard women say that as soon as the baby is born they forget all the pain of childbirth. Dare I say that it’s kinda like the same thing?

I’m sure I went through an exorcism or two, but I can’t remember now. It’s hard staring in the face of atrocity. More so for the writer, who has a duty to all his characters, even the ones he doesn’t like personally. Writing about any cruel event costs you. You can write about slavery, or the holocaust or the Armenian genocide but it will cost you. You can get lost in all that death and live a sort of death yourself. Or you can get so caught up in history that you forget that the world you just wrote about is behind you. I do know that I had to say goodbye to these characters and that was profoundly depressing. But I had to, especially when I found myself acting as if I was from that time and started giving some of my white friends hell, which now seems funny.

Writers should speak truth to power but it’s easy to get lost in your mission, so much that you forget that not everybody is either ally or adversary. I was at the panel discussion with some friends and a woman came up and started lecturing us about the plight of women in Muslim nations. Of course the situation in these countries is horrendous, but she had no interest in inviting us to share her view, but solely in beating us over the head with our collective male guilt, something I’ve never had the slightest trace of. So I asked her about the women who were being beaten to death in America, and what was she doing about that. And what was up with the culturally imperialist tone of her message, which seemed eerily similar to George Bush’s — that at the core of it was yet another first world person poking the “look who’s backward now” stick, to show how culturally superior she is. Let’s just say that no friendships were made that night.

Here’s my point. You have to be careful when you declare that you’re on a mission. Sooner or later the mission becomes you and you become nothing. When you’ve said what you need to say, you have to let that go and trust that your words will resonate. Everything I’ve needed to say about slavery, every issue that I’ve wrestled with, is in the book. It’s not that I’m now going to shut up and never speak of these things again, but the book stands as my argument and now I’m free to speak about something else. Look around you. There’s an awful lot to talk about.