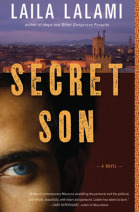

I’ve been looking forward to my friend Laila Lalami’s first novel since her story collection, Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits, was published back in 2005. Secret Son is finally out today, and — although, having witnessed its transformation over a couple of drafts, I’m not entirely objective — it’s well, well worth the wait.

I’ve been looking forward to my friend Laila Lalami’s first novel since her story collection, Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits, was published back in 2005. Secret Son is finally out today, and — although, having witnessed its transformation over a couple of drafts, I’m not entirely objective — it’s well, well worth the wait.

Youssef, who’s grown up in a tin-roof shack with his mother, learns that the father he believed dead is actually a wealthy businessman living nearby. No sooner does the boy become integrated into the man’s rarified but corrupt world, however, than he’s cast back to the slums, where people are now in debt to Islamic fundamentalists who provided aid after a flood when the government offered only empty promises. Below Lalami discusses what it was like to write such an extended work from a man’s perspective. Her insights are an interesting counterpoint to some of Marlon James’ comments, in last week’s interview, about the challenges of finding his way into his second novel, The Book of Night Women, which is narrated by a teenage girl.

I remember clearly the day I began working on the manuscript that became Secret Son. I was in the middle of revisions for my first book, and I wanted to try my hand at something new. When I pulled out my notebook and started scribbling, I had a blurry image in my mind of a young man, hands stuffed in his pockets, walking home to the shack he shares with his mother after watching a movie at a nearby theater. I followed that image and others like it, pixel by pixel, for the next five years, finding out more about this character as I went along.

Youssef — for that turned out to be his name — is a shy, bookish, gullible young man who learns that his dead father — whom he had always thought was a poor and respectable schoolteacher — is in fact a wealthy businessman living in the same sprawling city, Casablanca. Youssef sets out to find him and, much to his surprise, is welcomed into his father’s liberal, sophisticated, yet corrupt world and begins to learn that it isn’t possible to change who you are.

Now that Secret Son is being published, one of the first questions I get asked is, “What is it like writing from a male point of view?” I’m never sure how to answer this; perhaps it’s because I don’t think there is such a thing as a single, unified male point of view. I can only describe what it was like to write from this particular man’s point of view. There were some things about Youssef that felt extremely personal for me — for example, his attempts to negotiate various identities, classes, cultures, languages, and so on — and others that were not at all — for instance, his first sexual experience with a prostitute. But that was my task as a novelist; I had to use my imagination and my empathy to get at the sum of all those experiences.

Perhaps the reason I’ve never dwelled on the gender difference between my character and me is that I feel (with apologies to Flaubert) that Youssef, c’est moi. Youssef studies English at a university in Morocco (as did I); his mother is an orphan who was raised in a French institution in Fès (as was mine); he is gullible (as, unfortunately, am I); he speaks French fluently (as do I); yet he never quite feels at home with the French-educated élite (neither do I).

As a novelist, of course, I’ve used these details and shaped them according to the needs of my characters and plot. I made Youssef very poor and his father very rich to add more tension to their reunion; I had the mother lie about her origins because it seemed to fit with her character; I introduced temptations I was never exposed to; and so on. Overall, it’s been a wonderful experience, even though it was also sometimes difficult and even painful. So I don’t know what it’s like to write from a male point of view, but I do know how Youssef views the world and how he feels about it.