My friend John was taking a leak in a public restroom once when a middle-aged woman appeared out of nowhere and grabbed his cock.

My friend John was taking a leak in a public restroom once when a middle-aged woman appeared out of nowhere and grabbed his cock.

Now, John is the most professorial looking person I know, what with his white hair and matching beard and the natty hat he wears year-round, but he’s also the man who celebrated his 50th birthday by getting into a bar fight. He attracts freaks all the time. If the woman was thinking to intimidate him, she picked the wrong guy.

“Hey lady,” he said, knocking her hand away, “I’m still using that.”

Like John, I’m a weirdness magnet. I’ve been accused of pissing on a bodega floor, worn unfashionable comfort shoes to the hospital only to attract a foot fetishist, and, following recent surgery for a precancerous mole, was saddled with a neck bandage that brought out a whole new breed of perv. And it’s not just people. I once traveled to work with a roach in my pants.

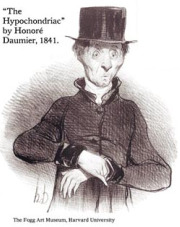

Something related that sucks: being a hypochondriac with health issues. Every time I run to the doctor clutching my heart or my side, or in a panic over waking up with a black tongue, I learn I must be imagining the thing, or that any fool knows you never take Pepto Bismol before bed. If I let something go, though, it’s inevitably a life-, limb-, or vision-threatening condition that will now be fifty times worse than it would have been if I’d just gone to the doctor right away, as any normal person would have done.

Sometimes a malady is nothing, then dire. Back in Tallahassee, I begged a dermatologist to remove the mole that’s since caused me so much trouble. He laughed. “That’s nothing,” he said. “It’s fine. And women’s chests scar horribly. Just come back if it changes.”

I saw him again the year following. Wasn’t the mole more irregular? Bigger? Darker? Didn’t he think it would be a good idea to take it off now?

He did not. He looked at me like I had twelve heads and made a notation on my chart.

Over the ensuing years, I thought of my mole whenever I saw pictures of melanoma. To my layperson’s eye, they looked suspiciously similar. But I remembered the doctor’s derision, and berated myself for being such a hypochondriac.

Finally, some seven years later, I went to a New York City dermatologist for a two-tone growth on my face.

“Oh, that’s fine,” he said. “But that mole on your chest, I have to biopsy.” (You already know the outcome of that.)

Recently God punished me for my lapsed vegetarianism by hiding a bone in the strips of chicken that topped my Caesar salad at a West Village restaurant I like. I don’t chew my food properly, so I didn’t notice the thing until I swallowed. There it was, lodged in my throat. A small group of friends were gathered for a going-away party, and I didn’t want to make a scene. I drank a few glasses of water, stood up, and sat down again. The bone didn’t budge.

Soon, I realized, I would die. I would choke, my friends wouldn’t know the Heimlich, and by the time the paramedics arrived I’d be flatlined. Maybe they’d revive me so I could spent the rest of my life diapered and drooling, and chained to an IV drip.

“Hey guys?” I said. “I think there’s a chicken bone stuck in my throat.”

The table sprang into action. Did I think I was choking? Did I need to lie down? Did I want to go to the hospital?

Dana, fortunately, knew an old restaurant trick: Crusty bread, to push the bone through. I ate three pieces, then five, then another basketful. No clear change, but maybe the bone was gone now. I didn’t feel anything unless I swallowed. Then I felt a mild irritation that could have been a scratch or sensation left behind.

Back at work, the feeling persisted. On the issue of seeking medical attention, I was torn. If I went to the emergency room, I would spend lots of money to learn, once again, what a delusional hypochondriac I am. But if I didn’t go, I would wake up choking at 3 o’clock in the morning.

So that’s how I wound up, one Friday night last month, sitting in the St. Vincent’s emergency room, possibly with a chicken bone caught in my throat, across from a Formidable Literary Figure (FLF) whom I’ve never met.

I was reading a not outstanding Patricia Highsmith novel. FLF was reading, too. I looked once, thought he looked familiar, looked back, and realized who it was.

This being New York, I’m sure there are people who would’ve enthusiastically introduced themselves, if not run home for their laptops to live-blog the entire event. But I had no interest in meeting this person in this context. We were both in the emergency room, after all, with ailments not visible to the naked eye. And mine was a chicken bone. Possibly an imaginary one. This was no time for a meet-and-greet.

I did not know whether FLF recognized me, or would have known who I was even if I’d been wearning a nametag, but I pulled out a larger book, a hardcover of Frankenstein that I could hide behind, and resolved not to make eye contact again lest I cause him discomfort.

Soon I began to relax. Don’t be such a stress case, I told myself. Under no circumstances will you and FLF have to say a single word to each other. I settled into my book, jotted down some observations about Mary Shelley’s writing.

Soon FLF closed his own book, got up, and left the room. Three seconds after the door swung shut behind him, a nurse confirmed his identity. She rounded the desk and called his name. Several times. She paced, shuffled the file, tried again. I said nothing.

She left; FLF returned. I sat in silence for thirty seconds, then forty-five. Not my problem, said the New Yawker devil on my shoulder. Not my place. We are all strangers here in the St. Vincent’s Emergency Room. No need to make everyone uncomfortable.

But what if FLF was in pain? What if he was getting ready to have a stroke, a heart attack, or a prolapsed intestine? What if FLF keeled over right in front of me? How would I live with myself then?

Experimentally, I cleared my throat. FLF looked in my direction. “I think they called you,” I said.

“Oh, did they?” Then FLF disappeared.

Later, in my curtained “room,” I relayed the details of my afternoon.

“So there’s a chicken bone in your throat?” the nurse said.

“Well, it feels like there is,” I said, although by that time, to tell the truth, it didn’t feel like much of anything at all.

The nurse gave me some water to drink and went away. Soon I heard her returning. “Any changes?” she called from the hall.

“No, as I say, I can swallow just fine,” I told her. “I don’t even know if the thing is still in there.”

“I’m not talking to you,” she said.

“No, no changes,” said the man in the next room, the man with a voice not unlike FLF’s.

Surely I hadn’t just recounted the chicken bone saga in this person’s earshot.

Several minutes later I heard the rustling of papers. “Okay, you can go now, [Mr. FLF],” the nurse said.

Later, after some inconclusive throat x-rays that showed “something weird there, but probably not a bone,” the nurse forgot to release me. I lay on my cot, reading, until a nice man came in and emptied the trash. A few minutes later someone shut out the lights.

On Monday morning — three days later — my doctor called. A bone had been detected in my throat, after all. An X-ray was scheduled. By then, naturally, the fragment was gone.