Poet Susan Ramsey and I have been corresponding for years, since she worked as a bookseller and I actually had time to answer my email, and she’s been urging me to read her friend Bonnie Jo Campbell almost that long. When I finally do crack the spine on American Salvage, I’m sure I won’t be disappointed. Ramsey is basically never wrong.

Poet Susan Ramsey and I have been corresponding for years, since she worked as a bookseller and I actually had time to answer my email, and she’s been urging me to read her friend Bonnie Jo Campbell almost that long. When I finally do crack the spine on American Salvage, I’m sure I won’t be disappointed. Ramsey is basically never wrong.

The National Book Awards judges might agree. Last month Campbell was named one of the 2009 fiction finalists.

Below, in advance of the final prize ceremony, Campbell talks with Ramsey about writing, mathematics, obsession, Flannery O’Connor, killing characters, drinking the Eastern European equivalent of Everclear, and untrustworthy chickens.

When nominations for the National Book Awards were announced in October, there was a double-dark-horse contender, Wayne State University Press’s nominee Bonnie Jo Campbell — a university press nominating a little-known writer. Though reports of her rookiehood have been greatly exaggerated (her collection Women and Other Animals won the AWP award and her novel Q Road was published by Scribner), A.S. Byatt hasn’t been sitting up nights worrying about her.

Still, the six-foot tall blonde in the Carhartt coveralls is, as Mel Brooks almost wrote, world-famous in Kalamazoo and when Maud invited me to interview her for the blog I jumped at the chance. I’d pulled garlic mustard with Bonnie Jo, I’d de-stemmed elderberries with her and argued books with her, but I’d never interviewed her. We met at Eccentric Café, usually a quiet place on a Sunday evening, but that night we’d hit their All Stout’s Day, and it was standing room only. We managed to score a couple of caustic red wines and huddled at a picnic table in the beer garden to talk about writing.

N.B. In order to shorten the transcript by half I have usually omitted the aside [laughter]. Imagine it preceding and following most questions. Tone is a truth like any other.

SR: You got a B.A. in philosophy followed by an M.A. Mathematics. How did an M.F.A. in Creative writing slip in there?

BC: Well, I always wanted to write, but writing is one of those fields where you come up against a lot of obstacles, and it seems like the writing isn’t going to pay off.

As opposed to mathematics?

Mathematics can pay off, actually — good jobs in mathematics. I always wanted to do creative writing, but I was just insecure about it, because everybody wanted to do it. It was like the handsome guy everybody wanted to have for a boyfriend — that was creative writing. And if they all wanted him, I didn’t want him. So I decided I would do math; that would show how smart I was.

But I always wrote, and I wrote all the time. I wrote essays, I tried different things. But after a couple of years in graduate school mathematics — I was in a PhD program, I took my preliminary exams and I did okay, I was in good standing, but I found I was just weeping all the time. Just weeping — every time I sat down to do some proofs I would just weep. So my PhD advisor told me maybe I should take a writing class, and that would make me feel better. And it did! My PhD advisor still says I’m one of his success stories, because I’m successful — I followed his advice.

So the intersection of mathematics and philosophy is creative writing.

[laughing] Well, no. That was the left side of the brain — wait, is the left side the analytical side? All my life I’ve gone to one side of the brain and then I’ve had to lean back to the other side. With creative writing, because there’s so much revising involved, and because there’s so much editing involved and because you have to just cut and ruthlessly analyze what you’ve written, you get to use both sides of your brain in writing. If you do it right.

Do you like the writing, or do you like the editing?

I like them both, but the revising is more satisfying because the outcome is better. When I just write — this is a secret I shouldn’t be letting out — I’m kind of a crappy writer, but I’m a really good rewriter. If you ever saw my first drafts you might wonder if I was in the right field at all.

You’ve said that in writing a short story you feel that you’re creating something akin to a mathematical proof. How’s that?

Oh, gosh, I get in trouble when people pay attention to the things I say. Well, let’s see: in a mathematical proof you have something you’re trying to show — and maybe on the first draft of a story maybe you don’t know what it is you’re trying to show. But once you get a draft of a story and figure out where you want to go, then your goal is to figure out the steps to get to the place where you’ve shown the thing. And in mathematics we’d say “prove” instead of “show” but maybe it’s not so very different. And in mathematics you do want to get there in the most efficient way possible, in fact the key words in mathematics are “elegant proof, everyone in mathematics is looking for an elegant proof. And short stories have to be very concise, and they have to be kind of — minimal. I don’t think it’s just a trend, I think it’s something in the nature of the short story, you don’t want to put a lot of extra stuff in there.

How is “minimal” different from “reductive”?

Yeah, well, I don’t want to say minimal as in “minimalist” — you don’t have to write Raymond Carver stories as edited by Gordon Lish. But in a short story you can’t really go off on too much of a tangent. If you are presenting material that goes beyond achieving the story that you’re trying to do, you really have to question whether it’s worth having it in there, whereas a novel can have arms and legs and extra limbs and be like an octopus and stretch out and go off on little adventures.

I’ve heard people say they like the writing but they sure wouldn’t want to meet the people in your stories, despite the fact that around here they do, every day of their lives, but the people in your stories don’t much read books. To what extent are you caught between a rock and a hard place, between these different kinds of people?

Well, sometimes the people in my books will read a book — if it’s mine, if they’re blood relations. But yeah, it is funny. I get my feelings hurt when everybody talks about my characters being so bad. I think, Who do they know? Do they just know gentle people who never have a harsh thought, who never have trouble in their lives? The reasons my characters are so hard, or so difficult, is because they have trouble in their lives, they struggle. And you know, it’s not easy to be with people who are struggling — but I think it’s worth it.

Often when I go to book groups it’s “Oh, they’re just terrible, and I think, I don’t know. They’re not so bad, are they? But I don’t know, the great thing about being a literary person, a reader, is that you get access to all kinds of lives, you get to be exposed to all kinds of things, and to choose to be closed-minded seems kind of foolish. I mean, readers have a choice — we get to be big-hearted if we want to.

You settled on the title American Salvage for the collection, then wrote the story to go with it, but it’s based on an actual incident that you’d already written about.

Yeah, it was very strange how this happened. I was trying to find a title for the collection, and it was getting closer to the deadline for the final manuscript. At Wayne State they were very flexible about making changes with me, bless them, and I was pitching around for a title, and I came upon, after many weeks of distressing all my family and friends, being a pain in the ass, trying out titles on them, finally this title that seemed to fit enough of the stories.

But to have a title with “American” in it’s a little bit dangerous, and I’m in some ways still a humble Midwesterner, even though I’m six foot tall and mean, so I was a little nervous about having a book entitled American Salvage without having a story that had that “American” in the name. And it just so happened that I’d written a nonfiction piece about somebody who works in a junkyard that sells American car parts and not foreign car parts, and I was just interested enough in this nonfiction piece, that I thought that there was a fiction piece living in there, that I thought I could just put myself to the test and write it.

And since that time you’ve written a poem about it, too. What role does obsession play?

Numerous poems. Obsession plays a very large role. I think that as writers our biggest tool is our ability to be obsessed with something. That is what we have, that is the big thing that we have. Because we all know people who write real fine, who write better than we do, but they don’t write, because they’re not compelled to. I don’t know if I’m saying that right. I just remember teaching great student writers who don’t care to write, there’s nothing telling them, “you have to write, you have to write, you have to write.” Being compelled to think and think and think and think about a story, and then wanting to work a story, wanting to work a thing you’ve been thinking about — that’s real obsession. And then it’s not enough just to think about it, but a writer wants to mess with it and work with it, change it.

And so having this challenge was kind of fun, like “what is the story within the real life story?” The nonfiction story was very much a condemnation of the person who committed the crime of beating up the tow truck driver. Oddly enough the story I wrote for American Salvage, a story titled “King Cole’s American Salvage,” is a story that has some sympathy for the criminal. And bless Alan Cheuse, that was his favorite story in the collection.

Speaking of Alan Cheuse, he wrote, “Because of their despairing feel and their shape, and their form, they feel quite lifelike.” Do you despair?

Other people despair more about the stories than I do. The thing is, for me, these characters appeared in my head, so I was more despairing before I wrote the stories because these characters were rattling around in my brain and I was all alone with them. So getting them on the page was, for me, a great relief, whereas for the rest of the public, I was inflicting my troubled characters upon them.

He also mentioned though, “Because of their despairing feel and their shape, and their form–” Shape and form?

Shape and form! That’s what we do in that revision process, that’s that whole mysterious business of turning what’s in our head into something someone might want to read. I don’t know why my stories come out in the shape that they do. It’s just one moment after another of revising telling me this is the shape they have to have. So I don’t make a conscious decision to say “Oh, I want this to have three scenes, and I want this to have a certain length.” I just write it how it comes out, and whatever maximizes the truth, that’s the shape I’ll go with.

One novelist refused to blurb your novel Q Road because you saved a character she thought should die.

That’s true. Yeah, I don’t know, I have a hard time killing folks, I really do — and I don’t want to go around killing kids if I can avoid it. I mean if I had to, if I had to, if the truth of the story required that I had to kill a kid I would do it, and, you know, Flannery O’Connor does it without a flinch. Of course, she knows God’s gonna save every kid she kills so she doesn’t have to worry.

The whole point of writing Q Road was, I wanted to form a family. I wanted to create a family out of three people who are very much alone in the world. And so my intention was different — I guess hers was just a misunderstanding of what I was trying to do.

But I have to abuse my characters sometime. They have to be heat-treated. They have to go through the forge, in order to be more worthy to live on the planet of my fiction. They have to suffer — and then they come out better.

So what role does hope play?

Hope? Gosh, I think hope is huge in all my stories. And not everybody sees it, again, people feel my stories are despairing, but despair has to be balanced by hope. I don’t think I’d want to write a story where I left a character without hope, I guess, but — I think I give them hope. Even the story where I abuse the guy the most, “The Burn,” oh, God, that poor guy, I had to put him through hell because he was so bad — he used the N-word and he was mean to the lesbians upstairs. But he wasn’t bad at his core, he wasn’t! But all that stuff that he picked up from his dad and from the guys at work — it all had to be burned off of him. It had to be burned off so he could get back to his core, at which he was an okay guy.

You won the Eudora Welty prize for short fiction from The Southern Review, but do you feel more in common with Flannery O’Connor?

I do. I’m with Flannery O’Connor and William Faulkner. Those are my guys. Although I’ve got to say, before I started writing I hadn’t really read Flannery O’Connor. The thing with Flannery O’Connor, nobody gets to be mean the way she is because she knows God is gonna save them — and I don’t know that. I might have to save them. I might be all these characters have.

About eighteen months ago you started writing poems that were unforgivably good from the get-go — so good that Kim Addonizio chose your chapbook“Love Letters to Sons of Bitches for The Center for Book Arts’ chapbook contest. What nudged you to poetry when you were being so successful with the short story and novel?

I don’t know that I was successful — I was feeling pretty dark about the whole fiction-writing thing. My agent had kind of pushed me away, I had these novels sitting around at home I was trying to work on, but feeling despair . So poetry was a great diversion. I think it was like a midlife crisis. It was like I’d decided to have an affair — only instead of having an affair away from my husband, I was having an affair away from fiction. And it was fun because I’d write these little stories — I call them little stories, but they’ve got line breaks, so they’re officially poems, but I’m toying with them, like playing with their little limbs, like they’re little dolls, or something, and it was so much fun, line by line and word by word and change a word and then giggle and then change a line around and make it rhyme and it was a pleasure! I still haven’t taken off my website the line that says I never, ever write poetry.

I think what prompted the poetry thing is I’d stored up all sorts of bits and pieces that didn’t work as stories and didn’t have anything to do with them, and then when I started writing poetry it was like, Wow, this little piece can go here, and this little piece can go there! And so I was writing, like every day I wrote a poem when I first started writing them. I’m not now, but for a year and a half I wrote a poem every day.

I like to stick to sonnets nowadays because I figure if it’s more than fourteen lines, I should write a story.

You’ve written that one incident as essay, short story, and poem. Does having more tools in your belt make it easier to find the right form, or are you gong to have to write a five-act play, a screen treatment and an opera libretto?

I think, with the junkyard story, I should! Now that you say that, I think I want to go home and do it right now, actually.

No, I love having all the forms to write in, I’ve got to say. It’s really a pleasure. And the nice thing about poetry is that it lets you write little things. Thank goodness for little things. But I do like to have all the forms. I mean, you’re serving the truth in all the different ways; in all the different forms you get at different angles.

You said that one story in this collection began in 1985. Are you persistent or just stubborn? Or is there a third, better choice?

You know, until I finished the story I thought I was just absurd to keep coming back to it again and again. I can remember in 1985 working on it. I lived in Boston, and I remember I was sitting at a desk on the third floor of my cousin’s rooming house. Actually, that’s how I met my husband; he was underneath the window with his old two-stroke motorcycle, where you have to mix the gas and oil so it just smoked and smoked and smoked…and I had the window open and the fumes just kept pouring in the window — I don’t know, guys and motorcycles. I ended up marrying him, so I guess it worked out.

What’s your default genre?

Fiction. I love the short story. It satisfies in every way. Short stories are short enough that you can get experimental without being tiresome. Very few experimental novels work, but you can write an experimental short story and it’s usually fun. You can stick with your characters for a while; you don’t have to marry ’em, you can just date ’em. Once you write a novel you’re married to those people, there’s no escape. And then of course you have to make up a few characters that you wouldn’t want to live with and that’s a problem. But short stories? You can put up with anybody for a while.

So what’s your typical working day like — writing included?

Okay, so I wake up — and I write. I actually make a pot of tea and pour it in a thermos and then make another pot of tea and bring it back, green tea, I make it real weak, I put cinnamon in it, and I sit at my desk and I try not to make noise ’cause I want my husband to keep sleeping because he’s in the room, and the wall between us is open at the top. So I write quietly, and I wear ear protectors so as not to be distracted by the lovely birdsong outside or to be distracted by my husband calling my name when he does wake up. How’s a girl supposed to write when the man she loves is lying in bed saying her name? So just plug along and I try to resist looking at e-mail.

I no longer have my e-mail hooked up to my writing computer because otherwise I check it all the time. Even if you think you want to do some research while you’re writing? Research is the biggest cop-out. Research is the main way to avoid writing. So I write in the morning until noon or one o’clock, I try to get three hours in, and then I have to go off and do the other things that are the day. I eat things and pick things and can things and feed donkeys and contemplate things and run errands. I love to run errands. Running errands is the best part of my day. And then once a week or so I get the blissful opportunity to write in the evening. Normally I don’t because I’m looking at student work, or reading — have to find time to read — but once in a while, in a blissful day, I get to write in the evening.

As a bookseller I always admired your ability to promote your books without being obnoxious, since in our experience self-promotion tends to be in inverse proportion to literary quality. [Ed. note: promotional items have included matchboxes, refrigerator magnets, temporary tattoos and a limited edition beer, “Q Brew.” But you say it has also given you hives, nervous tics, mysterious rashes, night sweats. Now, suddenly, the afterburners have kicked in and you’re not having to do all the promoting by yourself any more.

Like in the last three weeks. Maybe the third book’s the charm, in that I knew better what to expect. I actually developed eating disorders for my first two books — at least, I was overeating to relieve the stress. My first book, I didn’t know anything, but on the second book I decided I had to be a good marketer — and I did have Scribner’s excellent publicity department behind me, so that was nice, but I still did most of it myself (I was pretty small potatoes there at Scribner). With this book I promised Wayne State “I will sell this book, trust me!”

It was already in the third printing by the time of the NBA nominations?

Yeah, the third printing. So I did do everything I could. I did hire a publicist in Chicago to help me, she’s really swell, she’s my pal now — so I did do everything I could to promote it, but you’re right, you have to not be obnoxious. I mean that’s the trick, you have to tell people “Here, I hope you like my book, and I have reason to think it’s pretty good.” And you know, I’m from the Midwest, we don’t want to say our things are good but we kind of have to say things like “It got a starred Booklist review,” like, if you have the evidence, there’s a mathematical proof! But if you have any reason to believe your book isn’t good — then I guess you shouldn’t promote it. [laughter.]

You’ve taught writing a long time in a lot of venues, from universities [Campbell is currently on the faculty of the MFA program at Pacific University of the Northwest] to local libraries to the minimum security prison next to your vegetable garden. What’s the hardest thing to convince students of?

Every group of students needs to be convinced of something different. Those poor women in the prison needed to be convinced it was worthwhile just to pick up their damned pens. Just pick them up and put something down. Most people need to be told that their experiences in life are filled with stories that are worth telling. And the people at the library workshops are all bursting, wanting to write, but they think they don’t have anything interesting to say. They think “I want to write, but I don’t have any stories.” So for them I just encourage them, “Go to your families! Figure out what are the stories you tell in normal life? Like, get in touch with what you really –” Okay, Susan, I’m going to rephrase everything I just said, okay?

The main thing about writing that we miss is that we need to be in touch with what really gives us pleasure in reading and hearing stories. We often want to separate the literary stuff from the stuff that we love on a casual day-to-day basis with our friends and family. And I think we need to connect those things, the same way that a lot of classical music has got some folk music at its core, and then from the folk stuff you can choose to leave it as folk stuff or you can make it bigger and grander. So what the great literary story probably has at its core, the thing that makes it fabulous, is probably something that’s very small that comes from a “folk” place. I do think there is something to making that connection, to the real thing that gives us pleasure in stories, and not losing track of that.

Do you keep any kind of notebook?

I don’t have a writing notebook properly, but I do have this fabulous datebook that I keep with me at all times. [Hauls out a thick, red hardcover book the size of a novel.] The Big Red Book, the 2009 Standard Diary Daily Reminder. I do fill it up with writing stuff sometimes, but mostly it’s to-do lists — what I have to do and what I have to not forget. But when I’m on a train or a bus or watching a really boring presentation, then I do sometimes put creative things in there, but not very often. Mostly it’s very factual. They have them at Office Depot, and I get one every year. It costs way more money than it should — it’s like $25 or something, but it’s fun. My mother had these same books, starting back in 1960 when we were kids, so I was used to always seeing them on the shelf. Hers were more entertaining than mine are.

But you don’t look at them when you’re dry [Ed. note: i.e., stuck]? Or don’t you go dry?

Um. I guess once in a while I will. I use them for reference, usually. Like when I go to AWP and listen to panels I’ll write comments in the empty spaces on the wrong days’ pages, so you’d really have to work hard to find the stuff.

You had a phone interview from Dubai?

No, a print interview. Isn’t that something? She said she was interviewing all the finalists. She asked me about the bicycle touring company I used to run.

Goulash Tours.

Was that when you were sealing a deal by toasting in what you thought was vodka and turned out to be the Eastern European equivalent of Everclear?

No, that was my Polish business partner. I thought we were drinking vodka, but it was something more than that; it took away my ability to speak for quite a while. I had never had that experience before. We used the rest of that bottle to clean our bicycle chains; it was really effective, I’ll tell you.

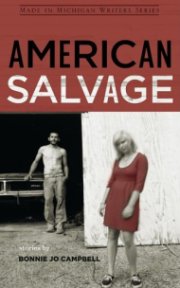

The link there is that Mary Whalen, photographer who did your cover, had me buy a bottle of Everclear for her when I was in Indiana (it’s illegal in Michigan); she uses it to clean glass negatives.

Everybody loves that cover. I tell everyone you used to say “red or a face,” when I told Mary that she just took the picture into the darkroom and colored the dress red. I hope she gets some good from this nomination, people seeing her work.

You’re pretty proactive about your covers, even though writers aren’t officially allowed to be.

Publishers kind of get tired of us fussing about the covers.

But you kept amiably suggesting possibilities?

In the end Wayne State was very open to my interest in the covers. Bless them. They had originally wanted to do an art cover, but I felt like these stories had to have a photograph on the cover.

And yet you were afraid that it would end up being a photograph of a junkyard.

I was deadly afraid that the cover of the book would be a junkyard with an American flag stuck in it. So I sent many notes to the poor assistant designer, Maya Rhodes, who, bless her heart, did continue to accept my e-mails. I was hoping the title font would look like signage, like a sign. And they did that.

How do people react to finding themselves in your stories?

I did have a story that was close to home for one of my brothers, and what he said to me after reading it was, “I didn’t know you understood.” And it made me feel good, because what I was trying to do in the story was create understanding for a terrible situation. Some situations in this book are very difficult, and think people who are in these kinds of situations feel very alone and they don’t feel that anybody can understand, and they certainly don’t think that any yahoo writing a book is going to understand.

American Salvage is from a university press, which is a long shot for an NBA award.

I would say.

How did that happen? How did you find out?

I found out a day before everybody else did, and I was sworn to secrecy. Can you believe? They told me I couldn’t tell. They said “You’re a finalist and you can’t tell,” and I asked if I could tell the donkeys and I could tell the donkey, and Chris, my husband. But I couldn’t tell the chickens, ’cause they couldn’t be trusted