Muriel Spark’s 1992 autobiography has been characterized as purse-lipped, sterile, and withholding, a manipulative account designed to settle scores and divert attention from anything unflattering.

Curriculum Vitae may be more factual than confessional, but judged on its own terms rather than by the standards of the contemporary tell-all, the book is a charming, idiosyncratic, and closely observed personal history, one that manages to surprise even as it turns out to be almost exactly what you’d expect the author of Memento Mori, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, The Comforters, and The Girls of Slender Means to offer up.

In an early passage, Spark explains the way children made tea in 1930s Edinburgh.

Sixty years ago is a short time in history. As recently as that I made at least one pot of tea for the family every day. It was delicious tea. Every schoolgirl, every schoolboy, knew how to make that exquisite pot of tea.

You boiled the kettle, and just before it came to the boil, you half-filled the teapot to warm it. When the kettle came to the boil, you kept it simmering while you threw out the water in the teapot and then put in a level spoonful of tea for each person and one for the pot. Up to four spoonfuls of tea from that sweetly odorous tea-caddy would make the perfect pot. The caddy spoon was a special shape, like a small silver shovel. You never took the kettle to the teapot; always the pot to the kettle, where you filled it, but never to the brim.

You let it stand, to ‘draw’, for three minutes.

The tea had to be drunk out of china, as thin at the rim as you could afford. Otherwise you lost the taste of the tea.

You put in milk sufficient to cloud the clear liquid, and sugar if you had a sweet tooth. Sugar or not was the only personal choice allowed.

Everyone who came to the house was offered a cup of tea, as in Dostoyevsky. What his method of making tea was I don’t know. (Tea from samovars must have been different, certainly without milk, and served in a glass set in a brass or silver holder.)

Tea at five o’clock was an occasion for visitors. One ate bread and butter first, graduating to cakes and biscuits. Five o’clock tea was something you ‘took’. If you had it as six you ‘ate’ your tea.

Tea at half-past six was high tea, a full meal which resembled breakfast. You had kippers, smoked haddock (smokies), ham, eggs or sausages for high tea. Potatoes did not accompany this meal. But a pot of tea, with bread, butter and jam, was always part of it.

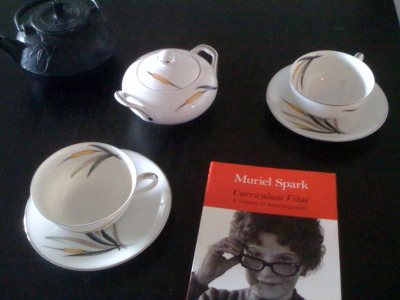

In my continuing quest to set the world record for dullness, tonight I’m picking up some sausages on the way home and following Spark’s instructions with the pretty tea set (above) that Lizzie gave me for Christmas. Too bad I don’t have any darning to do. Afterward, naturally, I’ll go out on the balcony and water my plants.