Paper Cuts’ comments about 19th century boardinghouses and bedbug infestations, and — as people take in roommates to pay the bills and the scourge makes a comeback — the likely impending rise of both, called to mind John Cheever’s bedbug travails, as recounted in Blake Bailey’s Cheever: A Life.

At the end of 1939, Cheever returned from a summer job to the “‘grey light of New York apartments.'” Soon, strapped for cash, he was living on Bank Street “despite having to sleep in the bathtub to avoid bedbugs.”

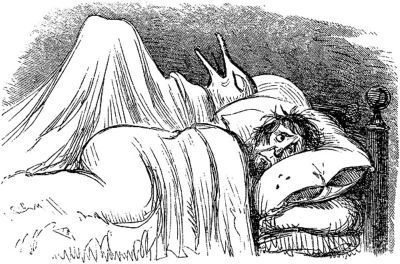

When not in the tub, he passed the time “lying in bed between stories, smoking and scratching his bedbug bites,” and indulging “in idle reveries about the kind of bon vivant he saw himself becoming.” By September 1940, “the bedbugs had become ‘ravening’ and carpenters descended on the place and began ‘pulling things apart.'” So he set off to join his wife-to-be in New Hampshire.

Nor was this Cheever’s last experience with the plague, which was prevalent in Manhattan even after the war. In the summer of 1945 the Cheevers were sharing a town house with some other families, and endured a “‘saga’ of ‘disorder, hysteria, and vermin'” — according to Cheever’s wife Mary — “‘that should be sung to the lyre.'”

One day Mary heard the unmistakable sound of a Flit gun being used the the Denneys’ room, and discovered that Ruth had been spraying a secondhand mattress she’d recently acquired, which explained the sudden infestation of bedbugs. Ruth Denney denied (and still denies) that bedbugs had traveled farther than her own room, but the other couples had already been bitten, and a terrible row ensued. Thus ended the unhappy experiment once and for all (though Cheever, at least, had a theme for his sixth and final “Town House” story).

If you’re a New Yorker subscriber, you can read Cheever’s story based on the experience here. ( “‘It isn’t that bad,’ Larry said. ‘They’re probably in the woodwork. It’s an old house. In the Army we had them all the time.'”)