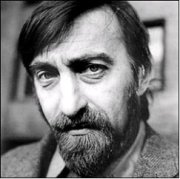

Jonathan Baumbach may be best known among hipsters as the dad who has a cameo in The Squid and the Whale, but more fundamentally he’s the experimental writer who co-founded the venerable Fiction Collective in the ’70s when his third novel, Reruns, was not picked up by the commercial publishers who put out his first two. After Fiction Collective published it, the book went on to sell more than any of his others, before or since.

Jonathan Baumbach may be best known among hipsters as the dad who has a cameo in The Squid and the Whale, but more fundamentally he’s the experimental writer who co-founded the venerable Fiction Collective in the ’70s when his third novel, Reruns, was not picked up by the commercial publishers who put out his first two. After Fiction Collective published it, the book went on to sell more than any of his others, before or since.

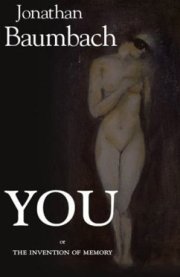

Now, thirty years later, Baumbach’s most recent publisher, like his last, has gone under, and in this case the enterprise went belly-up just months after his latest book, You, appeared. My friend Lauren Cerand was so passionate about You, she took Baumbach on as a publicity client despite the difficulties of reviving a book after the initial media window has closed. She and the author have started a site dedicated to the project.

Below Baumbach remembers the circumstances that led him and other writers to create Fiction Collective, and he compares the climate of 1974 with the dire situation publishing finds itself in today.

I got into my only publishing venture not for idealistic reasons (not at the beginning) and not for business considerations (least of all for that), but out of desperation. Reruns, my third and — at the time of its completion — best novel was rejected thirty-two times over a period of three and a half years. It was circulated by Candida Donadio, a literary agent of the highest reputation, and so had every chance to find acceptance.

I got into my only publishing venture not for idealistic reasons (not at the beginning) and not for business considerations (least of all for that), but out of desperation. Reruns, my third and — at the time of its completion — best novel was rejected thirty-two times over a period of three and a half years. It was circulated by Candida Donadio, a literary agent of the highest reputation, and so had every chance to find acceptance.

During the years that Reruns was almost, if not quite, making connection, I had difficulty getting into another novel. My first two novels had been taken by major publishing houses on first and third tries, and had their share of favorable attention. I had been spoiled in a modest way. Reruns may have been a departure from the first two books but it was also an outgrowth of what I had been doing, the inescapable, if not so obvious, next step. It was a breakthrough book, I supposed, a leap beyond where I had been and I had, fair to say, an excessive (and perhaps obsessive) attachment to it.

I began to talk to other writers whose work I admired about alternative means of publishing fiction. This was in 1973, a time when there were exceedingly few small press outlets for book-length fiction, and certainly none making its case to more than a handful of readers. It was not our idea to invent another marginalized small press. Our aspirations were naïve and inflated with quixotic enthusiasm. We wanted no less than to publish the best new fiction around and have it acknowledged as such in the media and carried in bookstores everywhere. We hoped to create something comparable to the wide-reaching writers’ cooperatives in Sweden and England, although there had been no tradition for it in the U.S.. In our unguarded expectations, we saw what eventually we called the Fiction Collective becoming the New Directions of our time.

At our early meetings, before we had a name, before we got to publish our first 6 novels in 1974, we analyzed the commercial publishing scene (which has worsened exponentially over the years) by sharing negative anecdotes. In addition to the old horror stories about how our books were not properly marketed (were not in bookstores when favorable reviews appeared) were new ones about editors admiring manuscripts, keeping them on ice for five or six months (I certainly knew about that) and then returning them because the writer had “a poor track record” or because the book was perceived to have “limited sales potential” or, with all good will, the house didn’t know how to present the book to the marketplace. Sometimes books were accepted only to have that acceptance revoked at a higher level. And then there were books that were out of print (shredded perhaps or incinerated, nowhere to be found) a year or so after coming to life.

Fiction that redefined the rules, innovative and experimental work, was having the most trouble finding a home in what was clearly (though defensively unacknowledged) a publishing establishment increasingly attuned to the bottom line. And why not? Publishers, like the rest of us, had to fill their stomachs and pay their bills.

I wrote a version of the preceding thirty-five years ago and updated it in 1999 as an introduction to an FC2 anthology. What we wanted then — the writers who created Fiction Collective (which has survived as FC2) — was not only to have the best overall list of fiction around, as Robert Coover said about us some years later, but to jostle the publishing establishment into taking more chances with work that was out on the edge. I couldn’t imagine Fiction Collective going on indefinitely. Our business, our busyness, was the writing of books. We were, I wanted to believe, a stopgap action in a period of emergency.

I was wrong on both counts. Fiction Collective (in the form of FC2) has continued to survive and corporate-controlled publishing has retracted its range even further. Some of our writers, most notably Russell Banks, have moved on with well-deserved success to larger venues. Others, myself included in the early days, eschewed commercial publishing for the advantage of keeping our books in print indefinitely — a commitment FC and FC2 have sustained.

Despite the emergence over the last 30 years of a plethora of good, if sometimes invisible, small presses, the emergency has become if anything more dire. The present financial crisis has made matters even more desperate.

It is hard (when you have no money) to sustain the publishing of original fiction in the U.S. and virtually impossible to sell books in significant number without the wherewithal to advertise and garner reviews.

Media is a system of mirrors that tends to discover and honor whatever it offered for discovery and honor in the first place. We are a culture in which the perception of something often counts for more than the thing itself.

My most recent small press publishing experience provides unwittingly an object lesson. My latest novel, You, was brought out by Rager Media, an ambitious press in Akron Ohio that was still in its infancy and, though decked out in running gear, had not quite learned to walk. For inexplicable reasons, the silence pervasive, books never seemed to find their way to review media until a terrific review by Steven Moore appeared in the Los Angeles Times. At long last, something was working, I thought, until I discovered through an intermediary that the reviewer had actually purchased his copy in a bookstore. Six months after the publication of You, Rager Media felt its only remaining option was to call it quits.

I have published 14 works of fiction in all, though none (including the first two commercially published novels) has sold as many books as Reruns. And the reason is not necessarily that Reruns found its audience, though I’d like to believe that it had, but that Fiction Collective as the first national literary publishing cooperative in the U.S. was news and so got considerable attention until it became, inevitably, old news.

This literary moment’s persuasive illusion is that fewer works that challenge the reader’s skills are being read. The reasons may be beside the point though they are everywhere apparent. Impatience seems high on the list. We want immediate payoffs for our commitments of time and concentration. Fiction, suggests the evidence, tends to be used more and more as a licit form of drug abuse.

Originality tends to generate difficulty in that it breaks faith with expectation, undermines the prevailing verities of last season’s fashion. Originality, by definition, takes us by surprise. Surprise is one of the touchstones of art. Literary art is always somewhat difficult during our first unescorted encounter with it. It often arrives without fanfare and without self-defining context.

It is probably fair to say that art sells only when it becomes an identifiable commodity. Commercial publishing tends to court literary work that is a thinly disguised variation on the recognizably artful — last year’s award winner tricked out to seem at once new and safely familiar.

An inevitable self-justifying cynicism pervades in an industry that knows in some secret pocket of denial that it is not doing its job. We are continually offered the cliche that there is nothing new by people who want to believe the new is really just the same old thing shrewdly disguised in this year’s marketing strategy.

Reading itself, reading anything, is an ambitious act in an age dominated by visual media. Even the simplest books require the translation of language into thought and image. Still what’s the point of reading work that is like television when television is tastier, more easily digested, and less time-consuming. If one reads books at all, shouldn’t one go for an experience one can’t get from TV or movies or anywhere else. Taking the trouble to read, perhaps we ought to go for something that throws our whole way of seeing into question. Art permits the dangerous in the comfort zone of the imagination.

Yet the system has its own self-referring logic. Books brought out by small presses, with little or no publicity budgets, which is to say little or no public identification, have virtually no hope of selling fast enough to earn space in the stop-and-shop bookstores. Review media unwittingly collaborate with the chain of circumstances that discriminates against fiction that does not conform to any of the prevailing verities. Media give extensive review space by and large to books publishers announce as important through, among other signifiers, commitment of advertising budget.

Even writers of established reputations who are not perceived to have large audiences (or audiences large enough to satisfy the multi-national corporations that own most publishing houses) pay the price.

Now I come with some trepidation to the argument implicit in this piece. What’s fun about reading fiction that refuses to yield itself without a struggle? Ah, fun! Still, I think it reasonable to say that the more active we are as readers, the greater the potential satisfaction in the reading experience. It’s a bit like love, but isn’t everything that matters?

It is not the resolution of difficulty that the ideal reader we imagine for ourselves is after, but the nature of the mysterious, mysteriousness itself.