Blake Bailey’s John Cheever biography isn’t out till next March, but an advance copy arrived in the mail a couple days ago, and I’ve been enjoying the author’s skillful and generous use of excerpts from Cheever’s massive journal.

The highlight so far (in that it reveals Cheever as an at-least-occasional black hole for praise) is an entry about the lunch Cheever had with Harper & Row editor Simon Michael Bessie after turning in his manuscript of The Wapshot Chronicle.

Bear in mind that the New York Times had this to say about the editor’s role in Cheever’s career on Bessie’s death four and a half years ago:

His reputation as an enterprising editor was burnished by a story John Cheever often told, about the publication of Cheever’s first novel, “The Wapshot Chronicle.”

As Susan Cheever recounts it in a memoir of her father, “Home Before Dark” (1984), Mr. Cheever had offered the novel to Random House in 1954, but the publisher turned it down. In despair, he rented a house that summer on Nantucket Island, took his family there and continued working on the novel. One day, as Cheever was staring out the window, a sailing yacht appeared in the harbor and dropped anchor. A man in white flannels and a double-breasted blazer was rowed ashore in a dinghy and announced in the voice of a literate aristocrat to the small crowd that had gathered to greet him, “I’m looking for John Cheever.”

“It was Simon Michael Bessie,” Ms. Cheever writes, “a senior editor at Harper & Row, and he had come to buy “The Wapshot Chronicle.'”

(Bailey provides some background on this episode — the two men had met at a Westchester party, and Bessie was in effect bailing Cheever out of an advance repayment debacle with another publisher that had given up hope of ever seeing the promised book — and suggests it didn’t happen quite this way.)

Although Bessie had pronounced the revised manuscript “wonderful” over the phone, he’d promised “detailed criticism” would follow in a letter, and Cheever had dismissed the praise, and fixated on and magnified the possible negative response until he’d begun to anticipate rejection. By the time they sat down across from each other at a Vanderbilt Hotel table, Cheever seemed determined to pave the way for it. “If you don’t really like the book,” he told Bessie, “I’ll be glad to give you back your twenty-four hundred dollars.”

“I tried to tell you for half an hour on the phone the other day what a wonderful book it is,” Bessie said. He spent much of the meal reiterating and expanding on the praise. Cheever, according to Bailey, appeared mollified, but made clear in his journal later that he was still unconvinced.

William Maxwell’s enthusiasm for The Wapshot Chronicle made the difference “between feeling alive and feeling like an old suit hanging in a closet,” and Katharine White’s “good opinion fortified me over the summer and made me a loving husband and a patient father. Without it I would have got drunk and broken all the dishes.”

Bessie, on the other hand, reminded Cheever

of other people who put one into the position of a patsy. They stuff you into taxi cabs, buy you plane tickets and buy you the drink you don’t need and in the end they leave you standing alone at the bar, surrounded by your luggage and screwed.

More notes: In his journal, Cheever often referred to himself in the third person, using alter egos such as ‘Coverly,’ ‘Bierstubble,’ or ‘Estabrook.'”

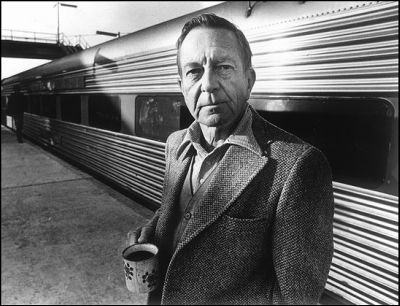

Image taken from John Cheever Reseñas.