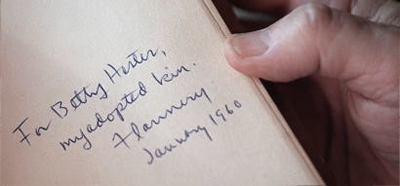

Betty Hester, longtime correspondent, friend, and “adopted kin” to Flannery O’Connor, donated the letters she received from the Southern writer to Emory University in 1987, with the stipulation that they remain sealed for twenty years.

In 1998 she committed suicide with a hollow-nose bullet aimed at her skull, after spending the afternoon eating a day-late Christmas dinner and playfully mocking William Sessions “for taking the Church seriously.”

Hester (pictured at right) also exchanged letters with Iris Murdoch and wrote bundles of unpublished stories and novels, and a philosophical treatise. She was originally known to O’Connor scholars only as “A.” Her identity was disclosed after her death.

Hester (pictured at right) also exchanged letters with Iris Murdoch and wrote bundles of unpublished stories and novels, and a philosophical treatise. She was originally known to O’Connor scholars only as “A.” Her identity was disclosed after her death.

Yesterday O’Connor’s 300 letters to Hester — which reportedly reveal the writer’s attitudes about subjects from civil rights to homosexuality — were finally made public.

According to Emory’s Steve Enniss, the early missives center on the two women’s faith. In the course of their correspondence, the reclusive Hester converted to Catholicism, asking O’Connor to be her sponsor, but left the church in 1961.

Last week Enniss speculated that Hester ordered the letters sealed because of her sexual orientation.

Betty was a lesbian, and probably for that reason was worried about public scrutiny of herself. She didn’t want any attention. She did not want scholars knocking at her door and did not want to answer meddlesome questions…

I believe Flannery will appear [to readers of the letters] in a very caring way in relation to Betty Hester’s disclosure about her personal life…

I’ve transcribed one of two brief excerpts read by Enniss on All Things Considered yesterday. Obviously the punctuation of the original will vary.

This excerpt is from a response to Hester’s revelation that she watched her own mother commit suicide at age 13. Hester also appears to have revealed some past sexual liaisons, which may have led to her dishonorable discharge from the army. O’Connor wrote:

Compared to what you have experienced in the way of radical misery, I have never had anything to bear in my life but minor irritations — but there are times when the worst suffering is not to suffer, and the worst affliction, not to be afflicted. Job’s comforters were worse off than he was, though they did not know it. If in any sense my knowing your burden can make your burden lighter, then I am doubly glad I know it. You were right to tell me, but I’m glad you didn’t tell me until I knew you well. Where you are wrong is in saying that you are the history of horror. The meaning of the redemption is precisely that we do not have to be our history, and nothing is plainer to me than that you are not your history.

Whether the history to which O’Connor refers is Hester’s sexual background, Enniss did not say.

Other Flannery O’Connor reading:

Added 5/15/2007: The AJC summarizes O’Connor’s remarks, in the Hester correspondence, on other Southern writers:

She quips that the French seem to think that fellow Georgia writer Erskine Caldwell is Shakespeare. She calls Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird, a child’s story, and writes she can “barely force my way through” Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

Images of inscription and of Hester taken from the AJC.