“I think my great handicap is my insistence on freedom,” Dawn Powell once wrote. “I require it. So I cannot make the suave adjustments to a successful writer’s life — right people, right hospitality, right gestures, because I want to be free.” Rudolph Wurlitzer, like many fine writers, could say the same.

The screenwriter behind the landmark 1973 film Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, whose work arguably inspired Jim Jarmusch’s 1995 film Dead Man, Wurlitzer is also a novelist. Erik Davis calls his remarkable new book, The Drop Edge of Yonder, “the most hallucinogenic western you’ll ever catch in the movie house of your mind’s eye,” “a Queen of Hearts sutra, a court jester’s Blood Meridian.” (Sample the book here.)

My friend Lauren Cerand, Wurlitzer’s publicist, correctly predicted I’d be wild about The Drop Edge of Yonder. And she says I’d have an affinity with Wurlitzer the man, too. “He hates the dog and pony show,” she told me.

I asked if he’d be willing to talk about that, and voilà. Below Wurlizer writes about his allergy to commercially dictated art.

After my first novel, Nog, was published it soon became clear, given the cult status the book had been assigned, that it would be difficult if not impossible to continue writing novels unless I had a day job. Having an aversion towards the traditional rigidities of the academic world as well as not having any worldly money making skills, I was faced with driving a cab, or bartending, or dealing drugs, or finding a rich girlfriend, or remaining crouched in the corner, or worse. I was rescued from this precarious situation by Monte Hellman, a maverick director who was trying to finance Two Lane Blacktop from a conventional script about a mechanic and driver who drift around the country racing a hot rod.

After my first novel, Nog, was published it soon became clear, given the cult status the book had been assigned, that it would be difficult if not impossible to continue writing novels unless I had a day job. Having an aversion towards the traditional rigidities of the academic world as well as not having any worldly money making skills, I was faced with driving a cab, or bartending, or dealing drugs, or finding a rich girlfriend, or remaining crouched in the corner, or worse. I was rescued from this precarious situation by Monte Hellman, a maverick director who was trying to finance Two Lane Blacktop from a conventional script about a mechanic and driver who drift around the country racing a hot rod.

After reading Nog, and sensing that I might be a kindred spirit, Monte offered me the job of rewriting the original script into something he had never read before, an unusual request that I would never be presented with again, at least not in the world of commercially dictated films. After Two Lane Blacktop came out I was asked to write Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid for Sam Peckinpah, a pay day which enabled me live off the grid long enough to write Flats, an even more obscure novel than Nog.

Exausted, broke, and once again dazed and confused, I tried my luck in L.A., trolling for another script gig in the lock-down sublimated rituals of the increasingly corporate mono-cultural film business. Finally after a year or more of sliding back and forth from the high to the low road and back again, I managed to put enough coin on the table for another novel. The effort, appropriately titled Quake, involved a huge earthquake that destroyed most of L.A., not only physically but emotionally and psychologically. I realized later that the book represented not just a metaphor but a catharsis that dissolved the seductive illusions I had grown attached to in my increasingly long nights and short days of California dreaming.

The dream lasted through the seventies and early eighties, then faded as interesting jobs became harder to find much less survive, and the game became so alienating and weird that the whole process took three or four times as long to complete: pitching, then waiting, then pitching again, then finally writing, then rewriting, then waiting and writing again until I collapsed in brain fog, not knowing what I thought or felt. It was no longer possible to continue lurching back and forth from internal novelistic preoccupations and doubts to the worldly strategies of survival that go with mono-cultural lowest common denominator collaborations where language is sublimated to image, and instinct and imagination abandoned to sales driven agendas.

When I began to feel like I was tap dancing on a rubber raft, I drifted to Europe, finding work with independent directors such as Antonioni, Bertolucci, Volker Schlondorff and Alex Cox, as well as, off and on over a twenty year friendship, collaborating with Robert Frank on two short films and one feature, all made in New York and Nova Scotia. Making a film with Robert Frank always renewed my energies and enthusiasms, creatively and spiritually.

After I finished my last novel, The Drop Edge of Yonder, it became clear that my old ways of surviving no longer applied and that the culture had so radically changed that I had no choice but to close the door to past solutions. Mainstream entertainment seemed to be increasingly represented by broken and cynical engines of corporate commerce.

When the first responses from my old publishers were confusion if not actual bewilderment I gave up trying to enter or be a part of the Big Room. I pulled back and waited, gradually realizing that to go on at all the process would have to involve writing for its own sake, without attachment to monetary results or established recognitions. I was surprised when the sense of futility was replaced by freedom and curiosity, sensations that I hadn’t experienced for a very long time.

In the early days when I first began to write, I wrote mainly in the present, for its own sake, without the habits that go along with hope, and thus the process was largely one without fear. I wrote to survive, to create a personal language, and, of course, to find a way to communicate beyond the habitual dictates of my discursive mind stream, even if the result was received by only a few people.

Out of the blue, I was approached by a young publisher who had started a small press called Two Dollar Radio. He had read my book and was eager to publish it. At first I was apprehensive, not knowing if he at all knew what he was doing. But the enthusiasm was disarming and stubborn and I gradually felt that in some way I had come full circle, that this was what I was meant to do. Two Dollar Radio was founded and run by a young husband and wife team, Eric Obenauf and Eliza Jane Wood. Their expressed ambitions were not only to survive but to publish without compromise what excited them and what they believed in. Their main focus was towards innovative and original fiction and they were eager to proceed in a way that wasn’t compromised by the usual reductive corporate strategies that lately have seemed to more and more define what remains of the larger main-stream publishing world.

It was clear from the jump that they were determined to hold to their vision with not only passionate endurance, but with rigorous integrity, even it meant working part time in a restaurant or taking in independent proof and editing jobs. Even though my previous novels have been published by the Big Players, including Random House, Knopf and Dutton, I haven’t missed those houses’ views and strategies about books and readers, which reminded me of the Hollywood movie studios. Entering the world of Two Dollar Radio, no matter how innocent or naïve their initial enthusiasms, represented a chance for a different more friendly and creative process, one that involved radically new methods of distribution and communication, including the new expanding world of blogs on the far reaches of the Internet.

The Mom and Pop team that drove the engine of Two Dollar Radio was also open to collaboration and eager to learn, and it was satisfying as well as nourishing to help design the book’s cover, and to enter into a real dialog about the complexities and possibilities of publishing in a new way. Also, for the first time, I didn’t mind doing “readings,” or giving interviews, or breaking bread with the publishers, because it was more a team process.

My on-going adventure with Two Dollar Radio, whose editors are now commited to re-releasing some of my old books, is one that I wouldn’t change, not even for money, or at least, well… yes, at this point, not even for money.

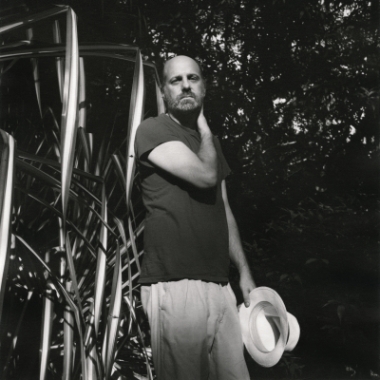

Photo of Rudy Wurlitzer in Havana, 1987, copyright the magnificent Lynn Davis, Wurlitzer’s wife.