No doubt David Grann’s utterly riveting Letter From Poland was the talk of the blogosphere when it appeared last month, but I only just rescued that issue of The New Yorker from the box of mail I packed up to move, and I spent an hour I couldn’t spare on this story about a brutal murder perpetrated in November 2000, in the southwest corner of Poland.

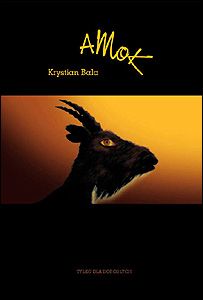

The case of Dariusz Janiszewski, a businessman whose brutalized corpse washed up in a river, had gone several years’ worth of cold before a new detective reopened the file. He discovered that the victim’s cell phone, missing since his disappearance, was sold on an Internet auction site even before his body was found. Stranger still, while the file had been gathering frost, the seller, “Chris,” A/K/A former philosophy student Krystian Bala (above), had published a novel, Amok, “which encapsulated all his philosophical obsessions.”

The book depicts a murder by stabbing. That’s not the way Janiszewski died, but the narrator-killer, also named Chris, sells the weapon, a knife, “on an Internet auction.”

The book depicts a murder by stabbing. That’s not the way Janiszewski died, but the narrator-killer, also named Chris, sells the weapon, a knife, “on an Internet auction.”

These are only the first convergences that led the police toward the conclusion that an unholy mixture of postmodern theory and garden-variety jealousy propelled the narcissistic author to murder, and to celebrate the crime in fiction.

The story mirrors “Crime and Punishment,” in which Raskolnikov, convinced that he is a superior being who can deliver his own form of justice, murders a wretched pawnbroker. “Wouldn’t thousands of good deeds make up for one tiny little crime?” Raskolnikov asks. If Raskolnikov is a Frankenstein’s monster of modernity, then Chris, the protagonist of “Amok,” is a monster of posmodernity. In his view, not only is there no sacred being (“God, if you only existed, you’d see how sperm looks on blood”); there is also no truth (“Truth is being displaced by narrative”). One character admits that he doesn’t know which of his constructed personalities is real, and Chris says, “I’m a good liar, because I believe in the lies myself.”

Unbound by any sense of truth — moral, scientific, historical, biographical, legal — Chris embarks on a grisly rampage. After his wife catches him having sex with her best friend and leaves him (Chris says that he has, at least, “stripped her of her illusions”), he sleeps with one woman after another, the sex ranging from numbing to sadomasochistic. Inverting convention, he lusts after ugly women, insisting that they are “more real, more touchable, more alive.” He drinks too much. He spews vulgarities, determined, as one character puts it, to pulverize the language, to “screw it like no one else has ever screwed it.” He mocks traditional philosophers and blasphemes the Catholic Church….

Finally, Chris, repudiating what is considered the ultimate moral truth, kills his girlfriend Mary. “I tightened the noose around her neck, holding her down with one hand,” he says. “With my other hand, I stabbed the knife below her left breast…. Everything was covered in blood.” He then ejaculates on her. In a perverse echo of Wittgenstein’s notion that some actions defy language, Chris says of the killing, “There was no noise, no words, no movement. Complete silence.”

In “Crime and Punishment,” Raskolnikov confesses his sins and is punished for them, while being redeemed by the love of a woman named Sonya, who helpts to guide him back toward a pre-modern Christian order. But Chris never removes what he calls his “white gloves of silence,” and he is never punished. (“Murder leaves no stain,” he declares.) And his wife — who, not coincidentally, is also named Sonya — never returns to him.

It is possible, as Grann argues, to read the book as a kind of confession.

Bala himself, however, has refused to admit wrongdoing. When detained for questioning, he claimed he was beaten, and argued that he was being persecuted for his art — for his narrative working-out of difficult and troubling philosophical concepts. International PEN got involved. The Polish Justice Ministry “was deluged with letters on Bala’s behalf from around the world.”

Now awaiting a retrial after a prior conviction was overturned, Bala continues to maintain his innocence. “What is happening to me,” he says, “is like what happened to Salman Rushdie.” Meanwhile, the evidence against him is still mounting. And I’m waiting for the next edition of Peter Brooks’ Troubling Confessions: Speaking Guilt in Law and Literature.

Photo of Bala lifted from Time.