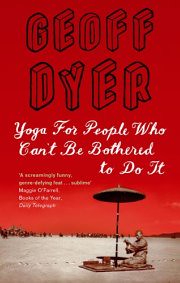

Geoff Dyer’s Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It coasts into and out of asides about the consolations and difficulties of writing, about the many books he started, or thought about starting, on his travels but didn’t finish.

Geoff Dyer’s Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It coasts into and out of asides about the consolations and difficulties of writing, about the many books he started, or thought about starting, on his travels but didn’t finish.

“Whenever a publisher asks me what I’m going to do next,” he told John Crace a couple years ago, “I say, ‘Whatever the fuck I want.’ After all, it’s me that’s going to be stuck indoors doing the hard work, so I might as well try and enjoy it.” Part of that enjoyment — for him and for the reader — lies in pondering the relationship between writing, living, longing, and the mind.

In “Horizontal Drift,” a novel he’s writing compensates for his real-life failure to hop a freight train.

As I sat by the Mississippi one afternoon, a freight rumbled past on the railroad track behind me, moving very slowly. I’d always wanted to hop a freight, and I sprang up, trying to muster up the courage to leap aboard. The length of the train and its slow speed meant that I had a long time — too long — to contemplate hauling myself aboard, but I was frightened of getting into trouble or injuring myself, and I stood there for five minutes, watching the boxcars clank past, until finally there were no more carriages and the train had passed. Watching it curve out of sight, I was filled with magnolia-tinted regret, the kind of feeling you get when you see a woman in the street, when your eyes meet for a moment but you make no effort to speak to her and then she is gone and you spend the rest of the day thinking that, had you spoken, she would have been pleased, not offended, and you would, perhaps, have fallen in love with each other. You wonder what her name might have been. Angela perhaps. Instead of hopping the freight, I went back to my apartment on Esplanade and had the character in the novel I was working on do so.

When you are lonely, writing can keep you company. It is also a form of self-compensation, a way of making up for things — as opposed to making things up — that did not quite happen.

Later, in a different essay, he says, “For a while I contemplated writing a story about someone who absorbs other people’s memories, memories of their friends and the things that have happened to them, memories that become intermingled with his own; then I realized that the person was me and I had already written several stories like that.”

These interludes are quick but open-ended, self-mocking but also serious, raising questions to which answers emerge, if at all, only indirectly, when looking at the work as a whole. I particularly like this section, from “Miss Cambodia,” in which Dyer likens his companion’s uncertainty about when to begin calling herself “Circle” to the author’s difficulty of deciding (knowing? learning?) what to call fictional characters.

Before Circle became Circle, she was called Sarah, but in the course of our travels in Southeast Asia, names like Sarah and Jeff came to seem extremely boring. We kept meeting people called Vortex or Raven or Love Cat or — my favourite — Cloudy Bongwater, and so we decided that we too should adopt interesting names. But of course you cannot call yourself Circle until you have in some way become Circle, so although Sarah decided early on that she wanted to call herself Circle (after a little girl we had met in Goa and, in a surge of sentiment, briefly considered adopting), she had to wait for the right moment to assume this identity. Having said that, we were also aware that assuming the name can hasten the development of the persona. It was the same dilemma as that faced by writers seeking a name for their characters: it is no good calling a character Dave if he is not Dave, but equally, if you refer to a character as X as a temporary expedient, it will only impede his acquiring the characteristics appropriate to his name, which might well turn out to be Brett or Sebastian or Stan. Before she could become Circle, Sarah had to acquire a kind of circularity of identity, an in-my-beginning-is-my-end attitude to life, even, possibly, a stoner dippiness that was quite out of character. Or so we thought.

Dyer’s next book, Otherwise Known as the Human Condition, is out in March.