It’s going to be a Jean Rhystravaganza around here for a little while.

It’s going to be a Jean Rhystravaganza around here for a little while.

Next week Granta online will publish some correspondence between novelist Alexander Chee and me about Rhys’ affair with Ford Madox Ford, and the novels they wrote afterward.

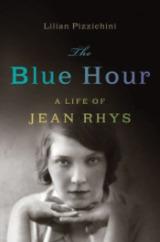

And today at The Second Pass, I review Lilian Pizzichini’s new biography, The Blue Hour: A Life of Jean Rhys.

Jean Rhys’ final novel and masterpiece, Wide Sargasso Sea, bestows a life on Jane Eyre’s offstage villain, the Creole madwoman in the attic. Although the book appeared to wide acclaim, Rhys held a grudge against editor Diana Athill for, she believed, publishing it prematurely. “‘It was not finished,’ she said coldly. She then pointed out the existence in the book of two unnecessary words. One was ‘then,’ the other ‘quite.'”

Rhys, who toiled on the book for many years, was always known for her economy. She learned early on to pare down her prose, shaping it until her stories seemed to echo the elusive emotional truths of her own experience. It was Ford Madox Ford, one of her lovers and her very first editor, who encouraged her in this cutting, but she took to the art so immediately and so zealously that he later urged her to emphasize geographical concreteness and include physical detail. Rhys only pruned further. The four slender, deceptively straightforward novels that resulted evoke, like nothing before and very little since, the anguish of pretty young women, living hand to mouth in seedy hotels and boarding houses, who are kept, used and finally abandoned by wealthy older men.

Restraint is as essential to Rhys as the depression and fear she excavates. The intensity of her work is counterbalanced by a steely precision that serves to stave off melodrama.

The Blue Hour: A Life of Jean Rhys, a brief biography by Lilian Pizzichini, reads more like a novel than a nonfiction study, and this is no accident. A foreword characterizes the book as “an attempt to recapture her life.” Passages from Rhys’ unfinished autobiography, Smile, Please, are liberally quoted and paraphrased. Conjecture as to her emotional state abounds. At times the clumsy armchair psychoanalysis weighs down the story, giving it the exaggerated sentimentality and cheap pathos of a romance novel, but the material itself is inherently fascinating.

The rest is here.