Theodora (Roosevelt) Keogh, the mysterious novelist, ballet dancer, wildcat owner, chicken farmer, and president’s granddaughter whose fiction inspires comparisons to Colette, was living in Paris with her first husband, artist Tom Keogh, when The Paris Review started up in the early fifties.

Theodora (Roosevelt) Keogh, the mysterious novelist, ballet dancer, wildcat owner, chicken farmer, and president’s granddaughter whose fiction inspires comparisons to Colette, was living in Paris with her first husband, artist Tom Keogh, when The Paris Review started up in the early fifties.

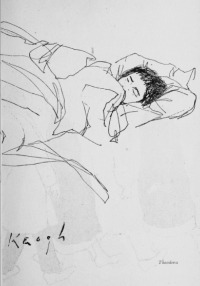

As I mentioned in The Week this summer, Tom’s drawing of Keogh (at right) appeared in the first issue of the magazine. Her own work, however, was never published there.

My favorite of Keogh’s novels, My Name is Rose, depicts a talented woman and unfaithful wife who, rather than focusing on her own art, has married a would-be novelist who works as a cultural critic. Like the new magazine that employs him, the husband has little native aesthetic judgment but is attuned mostly to the way the wind is blowing. His editor is likewise preoccupied with tracking all things hip.

After I found out about Tom’s drawing, and read what information is available about the doomed marriage, I began to wonder if Keogh wrote My Name is Rose partly to satirize the upstart Paris Review and its acolytes.

Joan Schenkar, author of the forthcoming Patricia Highsmith biography The Talented Miss Highsmith, became friendly with Keogh, one of few female writers Patricia Highsmith praised, while researching her subject. “I wanted to know,” Schenkar told me, “who could have produced a novel that impressed [Highsmith].”

The Talented Miss Highsmith arrived in the mail earlier this week. One fascinating passage — in which Schenkar revisits Highsmith’s praise for Keogh’s Meg, and explains why the book would have resonated with the steely Mr. Ripley author — incidentally lends credence to my intuition that Keogh didn’t care for The Paris Review.

It was in Queens, too, where Pat [Highsmith] joined a girl gang, another faintly delinquent experience she remembered with great pleasure in the last decde of her life. It was the “activity” of the gang — “they mostly ran around and had meetings, a lot of physical movement” — that Pat liked: the same active life she was later to admire so much in men. Her gang memories undoubtedly colored the wonderful review she gave to Meg (1950), a first novel by an ex-ballet dancer who also happened to be the adventurous granddaughter of a U.S. president. The ex-dancer’s name was Theodora Roosevelt Keogh and she lived in Paris with her husband Tom Keogh, resolutely refusing to give her publisher, Roger Straus, permission to trade on her illustrious name. A favorite of her formidable aunt, Alice Roosevelt Longworth, Theodora shunned The Paris Review crowd (they ignored her work as well, as they ignored the work of most women writers), and went on to write novels of such piercing sensual perception — a marriage of Colette and L.P. Hartley — that composer and diarist Ned Rorem remembers her from 1950s Paris as ‘our best American writer — certainly our best female writer.’

Pat wrote her review of Keogh’s novel Meg for The Saturday Review in April of 1950. It was Pat’s first published piece of criticism — one of the few reviews she would ever write about a work authored by a woman — and it is probably the most favorable review she ever published. The novel about which Pat was so untypically excited is a wayward work, with just the kind of heroine who would appeal to Pat: a preadolescent, androgynous prep school girl from the Upper East Side of Manhattan who carries a knife, dreams of being suckled by lions, blackmails her lesbian history teacher, runs with a wild gang of boys from the docks, and has a distinctly undaughterly reltionship with the father of one of her friends. In the last sentence of her critique of Meg, Pat left no doubt about how much of herself she saw in Theodora Keogh’s young heroine.

“Such an admirable personage is she with her banged-up knees, her dirty sweaters, her proud vision of the universe that, remembering one’s own childhood, one wishes one had kept more of Meg intact.”

See, previously: Keogh’s The Double Door; Keogh’s My Name is Rose; Highsmith on writing; and Highsmith’s snails.